Sabato 18 luglio 1573

On July 18, 1573, the Holy Tribunal of the Inquisition charged the artist Paolo Caliari – “Veronese” – with heresy and summoned him to defend his depiction of The Last Supper, painted for the refectory of the Dominican monastery of Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

What really happened on July 18, 1573?

What was really being discussed?

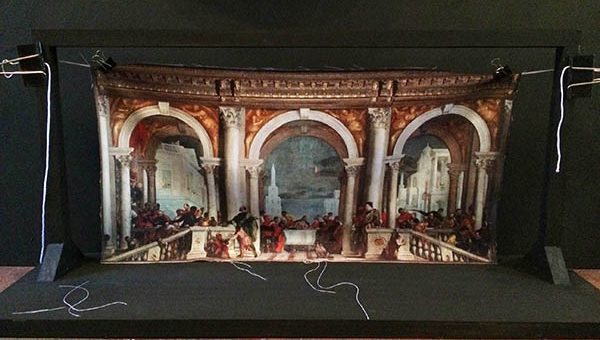

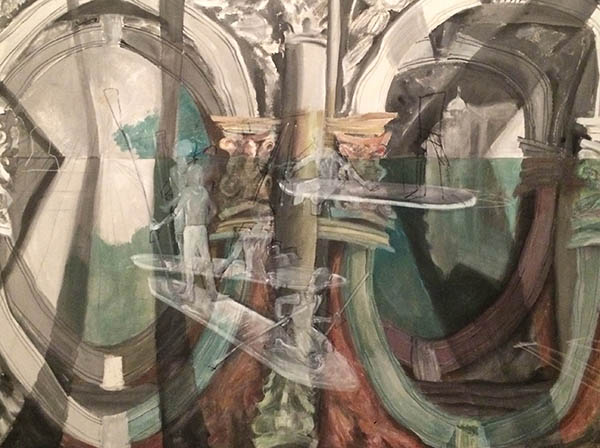

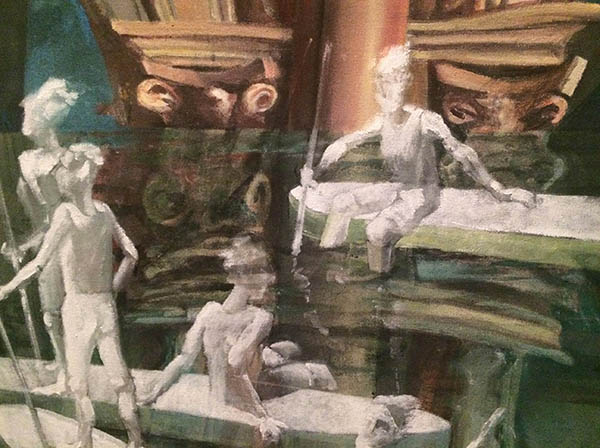

In this series of paintings, “Feast in the House of Levi” will serve as an abandoned city, whose buildings have lost their original meaning, a city altered by time and circumstance, a city visited by new beings who observe it, wander through it, and relate to it in an entirely unprecedented way.

Or not.

The history

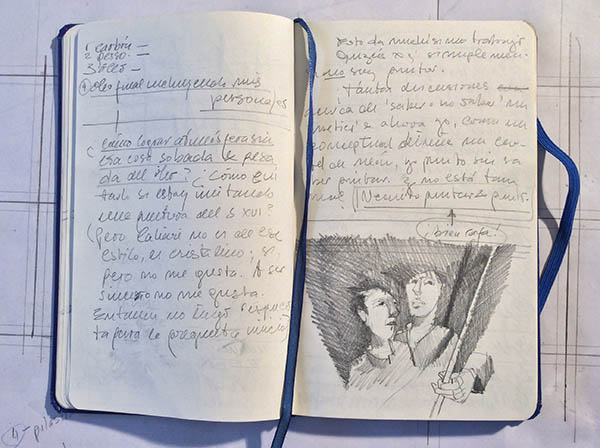

On July 18, 1573, the Holy Tribunal of the Inquisition charged the artist Paolo Caliari – “Veronese” – with heresy and summoned him to defend his depiction of The Last Supper, painted for the refectory of the Dominican monastery of Santi Giovanni e Paolo. That day, Veronese’s enormous canvas, which the Dominican order had commissioned – and presumably overseen – from this eminent artist of religious scenes, took center stage. He had run afoul of the Holy Office due to his inclusion of a number of characters and images deemed irreligious, according to the Inquisition’s “style manual.”

History tells us that the painter defied the Court, ardently defending his creative freedom and refusing to modify his work until, finally, the matter was settled with a name change: The Last Supper would thereafter become Feast in the House of Levi. A small price, considering Veronese had escaped the bonfire, but a clear edict, as well, about the proper representation of the Last Supper, which was endorsed by the addition of the title onto a pedestal in the right foreground of the composition – a gesture quite unusual for the time.

In this way, for centuries to come, July 18, 1573 has commemorated the birth of a myth, or one more example in a long history: the painter as romantic hero who challenges the forces of evil and remains unbowed, brandishing before that overwhelming power an ethereal, timeless force: Art. As recorded in his trial transcript, Veronese affirmed:

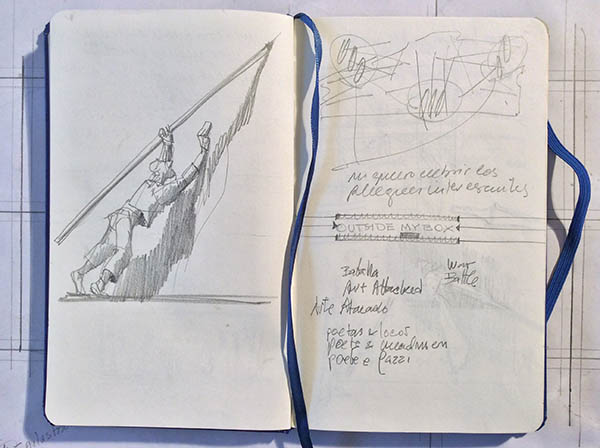

“We painters … take the same licenses that poets and madmen take ….”

That aura of self-confidence permeates the comic art of Milo Manara, or Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s poetry, especially where he imagines Veronese’s thoughts before, during and after the judgment as a kind of interior monologue, consolidating the myth with the artist’s rebellious last remark: “… Anyway, no one knows what the value of this work is.”

What really happened on July 18, 1573?

Was the heresy of a dog or a man with a toothpick sharing the scene with Our Lord Jesus Christ (and 52 other people) really debated? What was really being discussed?

And so, if we suppose that a tug-of-war between religious factions was the real reason for this interrogation, were the painting, the artist, or his so-called audacity ever at the center of this scene?

It is from these re-readings, these fresh appraisals, that the desire to return to the work itself – in short, what lasts – arises, in order to contemplate the painting itself, along with the intersecting questions of art/ the market/ power/ and historical context that interweave in perpetual reinvention for contemporary artists.

The project

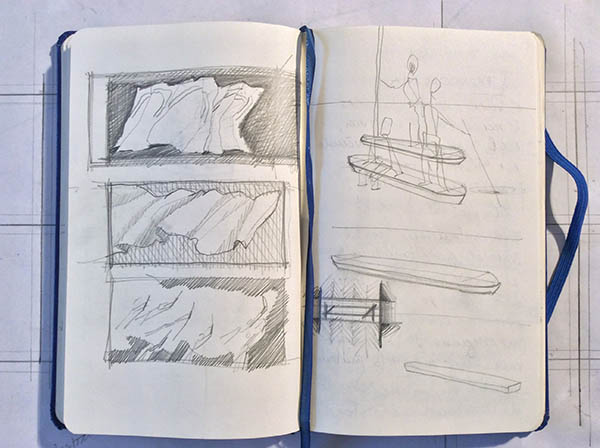

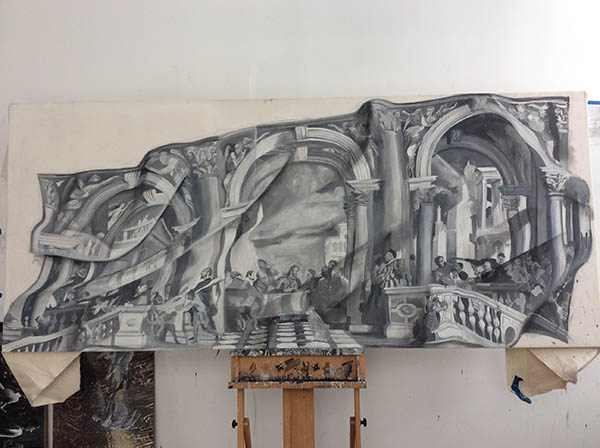

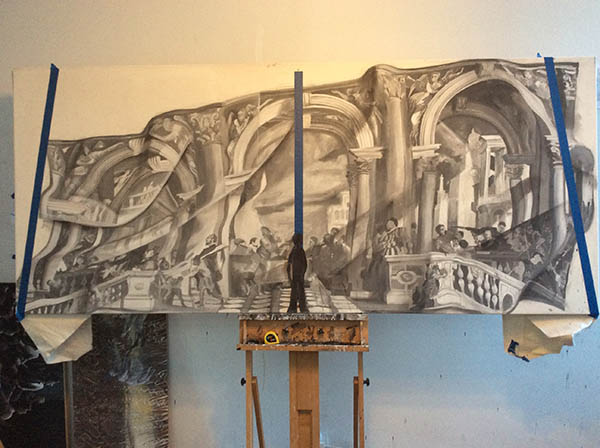

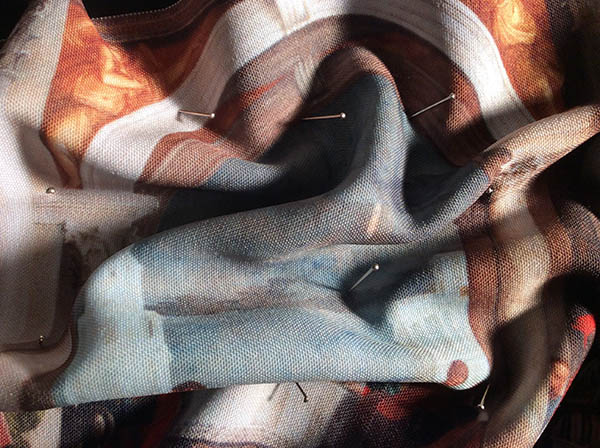

This series of paintings is entitled Saturday, July 18, 1573: the day on which the work, the painter and the powers of time gathered at an historic crossroads. Using that day as his starting point, Landea has taken that huge canvas and subjected the scene to various contingencies and challenges, as if Veronese’s painting had traveled through space and time to find himself faced with diverse societies that relate to him in contexts outside of Christianity. Other cultures, other civilizations, other beings from unknown societies, or those existing simultaneously in another ‘physical plane’ will face the work. What will they see?

Thus, Feast in the House of Levi will serve as an abandoned city, whose buildings have lost their original meaning, a city altered by time and circumstance, a city visited by new beings who observe it, wander through it, and relate to it in an entirely unprecedented way. Or not.

Analía Farjat

Translated by Anne Parris

Play Video

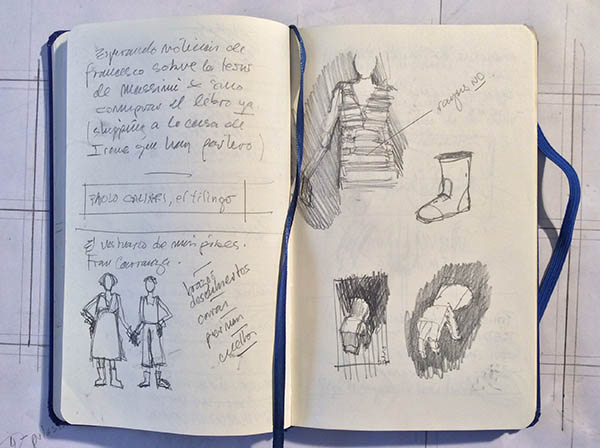

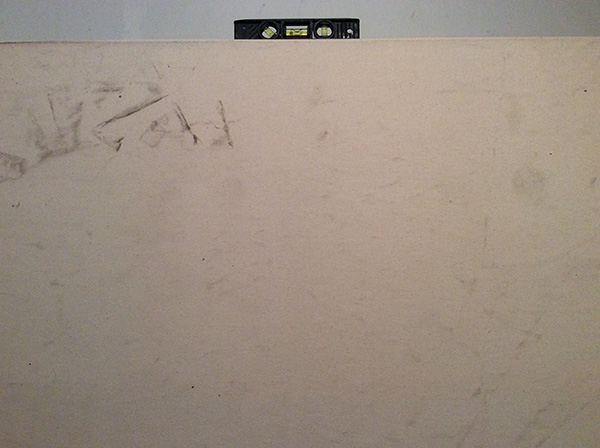

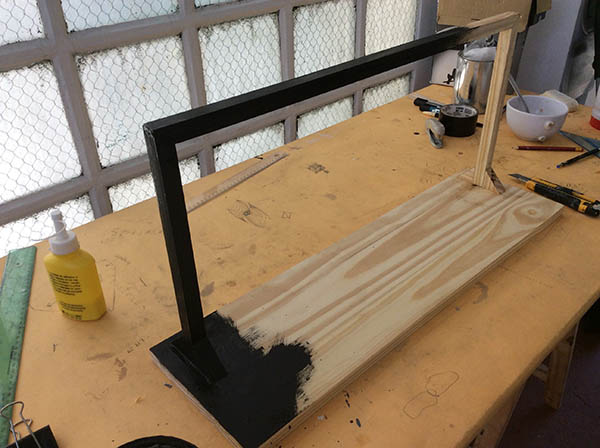

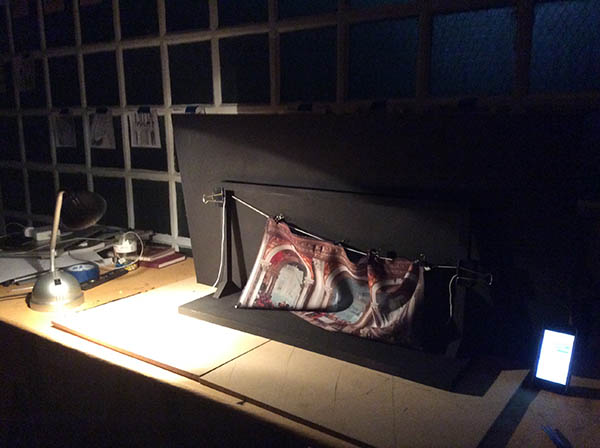

1573, process

Play Video

Rafael Landea received his MFA from La Plata University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is a 2011 recipient of a San Francisco Arts Commission Grant for Individual Artists and he was featured in the 2012 “Our Radar”, Creative Capital database of art projects.

His works are included in the public collections at MaM (Museum of Art and Memory), and MPB (Fine Arts Museum Buenos Aires) Argentina.

His most recent solo exhibitions were “1930” Buenos Aires Holocaust Museum, “Maps of Silence”, a multimedia installation at the Exploratorium Museum of Art Science and Human Perception in San Francisco, and “Malvinas” Museum Malvinas (ESMA) Buenos Aires.

Other solo exhibition venues include Grace Cathedral 1055 Gallery, San Francisco, CA, and, Archimboldo Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Group exhibition highlights include “Performance” at Gensler San Francisco, “Madres de Plaza de Mayo” CC Haroldo Conti, Buenos Aires.

Landea has worked as a set designer and painter for theater in Argentina for more than 15 years. He has also been actively involved in designing and producing murals nationally and internationally; the latest in San Francisco, funded by Artery Project, and collaborations in Turin and Genoa, Italy.

In 2019 created two large murals, Architecture University and the Law Library both in La Plata, Argentina.

He has created illustrations for magazines and books for important Argentinean publishers as Anfibia, Malisia, EME, Ediciones B, and Universities, the latest in 2021: “Malvinas mi Casa” a book based on a diary written in 1829 in Malvinas/Falklands.

Landea was selected for the 2020 Prequalified Artist Pool by San Francisco Arts Commission.

Rafael Landea received his MFA from La Plata University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is a 2011 recipient of a San Francisco Arts Commission Grant for Individual Artists and he was featured in the 2012 “Our Radar”, Creative Capital database of art projects.

His works are included in the public collections at MaM (Museum of Art and Memory), and MPB (Fine Arts Museum Buenos Aires) Argentina.

His most recent solo exhibitions were “1930” Buenos Aires Holocaust Museum, “Maps of Silence”, a multimedia installation at the Exploratorium Museum of Art Science and Human Perception in San Francisco, and “Malvinas” Museum Malvinas (ESMA) Buenos Aires.

Other solo exhibition venues include Grace Cathedral 1055 Gallery, San Francisco, CA, and, Archimboldo Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Group exhibition highlights include “Performance” at Gensler San Francisco, “Madres de Plaza de Mayo” CC Haroldo Conti, Buenos Aires.

Landea has worked as a set designer and painter for theater in Argentina for more than 15 years. He has also been actively involved in designing and producing murals nationally and internationally; the latest in San Francisco, funded by Artery Project, and collaborations in Turin and Genoa, Italy.

In 2019 created two large murals, Architecture University and the Law Library both in La Plata, Argentina.

He has created illustrations for magazines and books for important Argentinean publishers as Anfibia, Malisia, EME, Ediciones B, and Universities, the latest in 2021: “Malvinas mi Casa” a book based on a diary written in 1829 in Malvinas/Falklands.

Landea was selected for the 2020 Prequalified Artist Pool by San Francisco Arts Commission.