1930

“… any country, place, or society, whether with full conscience or in complete innocence, can be swept away by a collective blindness based on rumors and falsehoods”

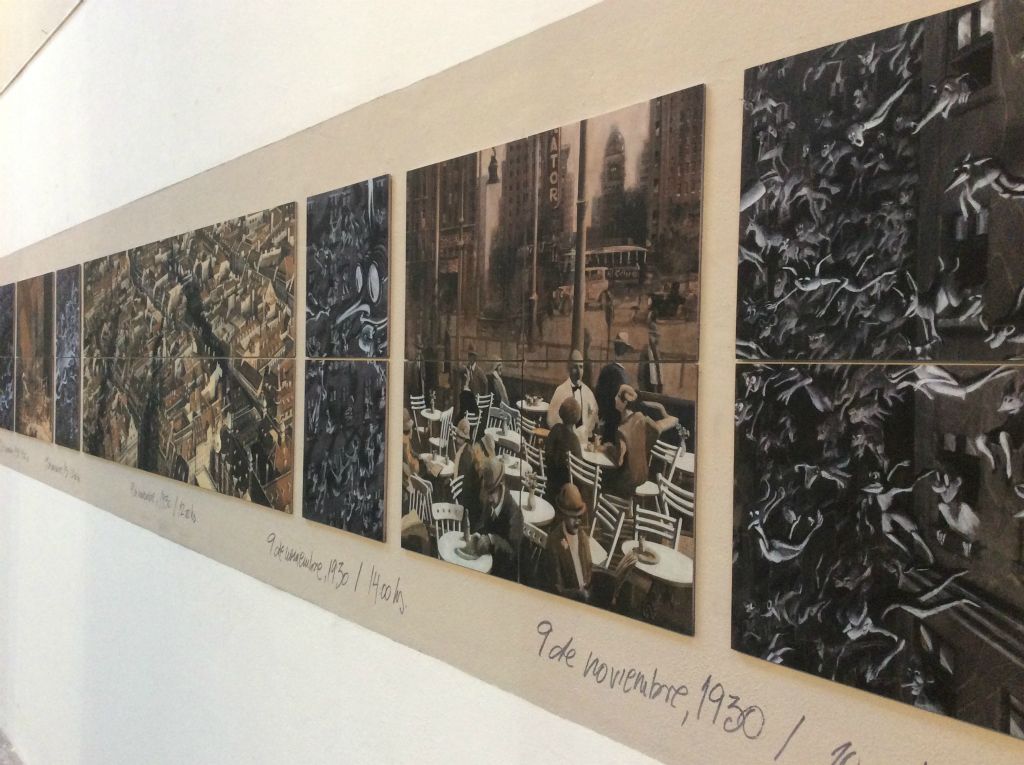

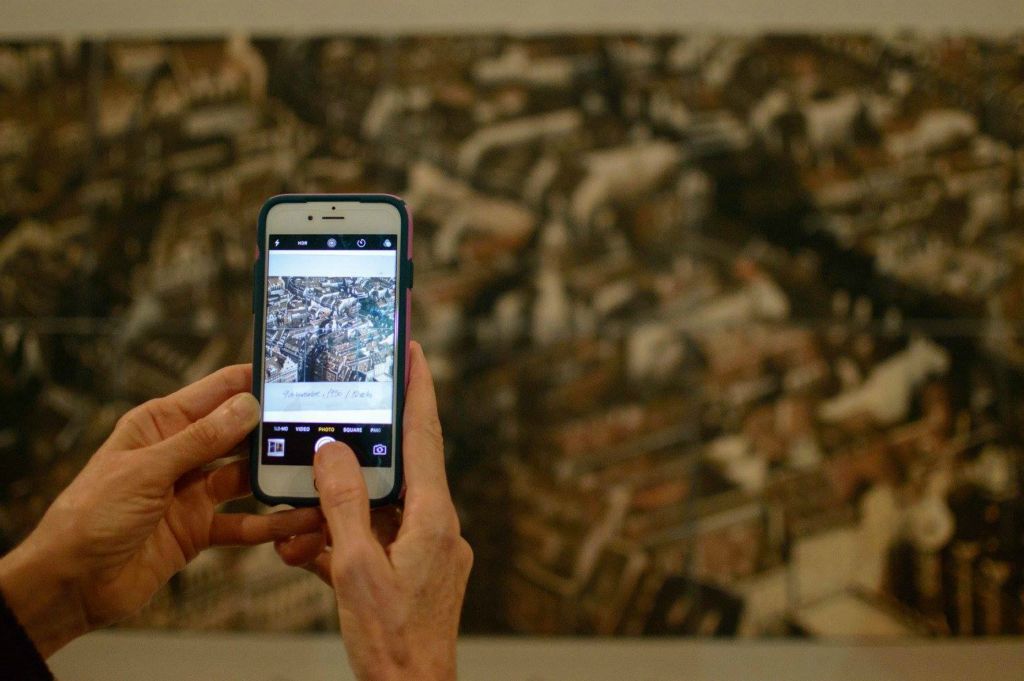

The installation, “1930”, is a collection of paintings of everyday life in Berlin inspired by scenes from two Weimar Era feature films: “Berlin: Symphony of a Great City” and “People on Sunday“. In what at first may appear as mundane urban scenes, a threatening presence slowly takes shape. Mysterious, misplaced shadows together with intertwined images of an imaginary rumor-driven monster (based on a drawing called “The Rumor” by Andreas Paul Weber) give a sense that something is broken. The installation presents a cross-section of German Weimar Era urban society captured by the ominous drumbeat of that time. In a larger sense, the paintings speak to how any country, place, or society, whether with full conscience or in complete innocence, can be swept away by a collective blindness based on rumors and falsehoods.

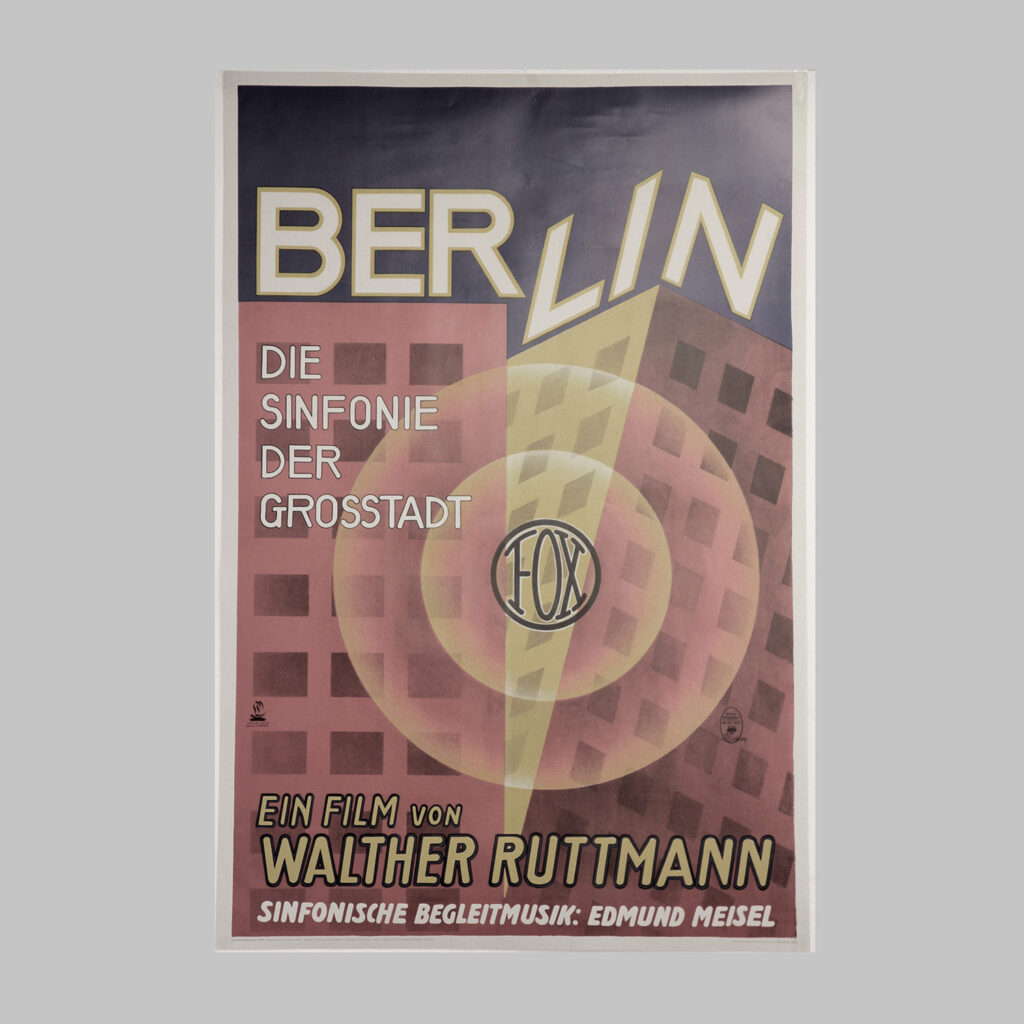

Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927); directed by Walther Ruttmann, script by Carl Mayer and Karl Freund.

This German silent film is an example of the city symphony film genre. The film portrays Berlin mainly through visual impressions in a semi-documentary style, without the narrative content of more mainstream films, though the sequencing of events shows us one day in Berlin, starting at early morning and ending deep in the night. Walter Ruttmann (1887-1941) was a German film director and an early practitioner of experimental film and best remembered for the film Berlin: Symphony of a Great City. Ruttmann was born in Frankfurt; he studied architecture and painting and worked as a graphic designer. His first abstract short films, Lichtspiel: Opus I (1921) and Opus II (1923), were experiments with new forms of film expression. He died in Berlin of wounds sustained when he was working on the front line as a war photographer.

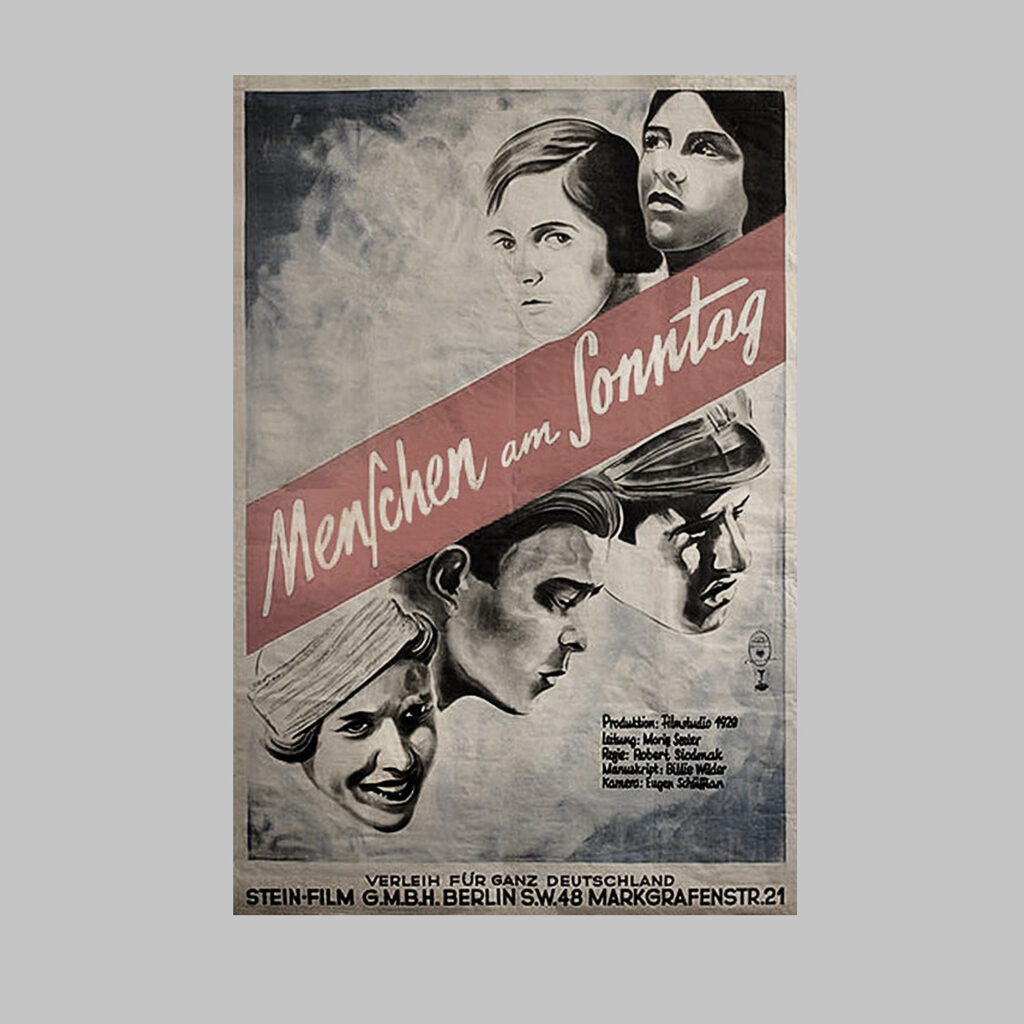

People on Sunday (1930); directed by Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer with script by Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak, and Curt Siodmak.

This was a German film director who also worked in the United States. People on Sunday was his first feature. With the rise of Nazism, Siodmak left Germany for Paris until Hitler again forced him out. Siodmak arrived in California in 1939, where he made 23 movies, many of them widely popular thrillers and crime melodramas, which critics today regard as classics of film noir. Edgar Georg Ulmer (1904-1972) was born in the Czech Republic. He lived in

Vienna, where he worked as a stage actor and set designer while studying architecture and philosophy. He moved to Los Angeles and began to direct films in 1933. His stylish and eccentric works came to be appreciated by film critics over the years following his retirement.

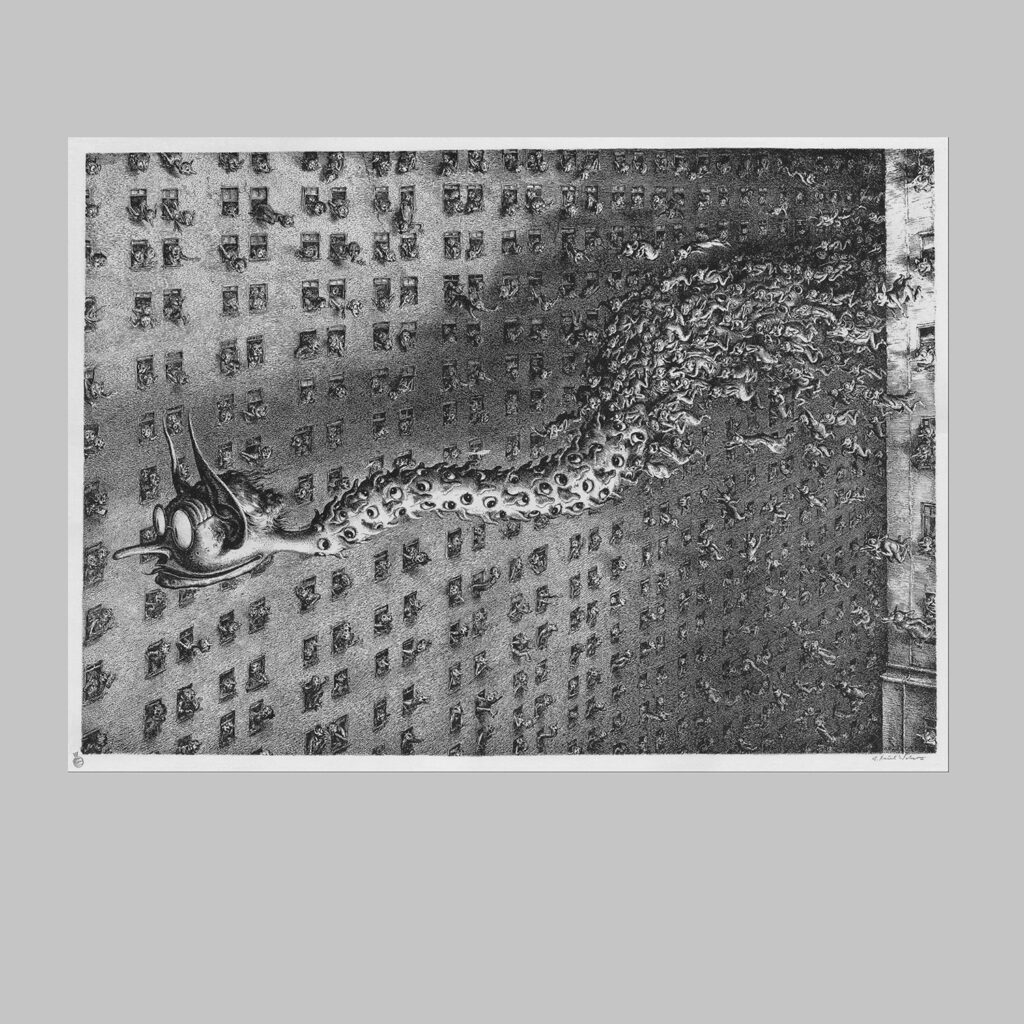

“The Rumor” by Andreas Paul Weber.

This drawing embodies the concept of rumor in the form of a dragon-like creature formed by eyes and tongues. First drawn in 1943 and later lithographed in 1953 for many the dragon represents a mob-mentality that fuels racism and discrimination. The viewer is left questioning the meaning of this dragon and whether the people shown in his drawing are willfully joining the creature or are being unwillingly forced to unify with it. A. P. Weber (1893-1980) was a German artist whose work specialized in political satire. He was co-editor of the “The Resistance, Journal for National Revolutionary Politics”. He produced illustrations, including the book “Hitler, a German Disaster” for which he was imprisoned in 1937. At least two of his images were used as Nazi war propaganda, as well as some of his earlier ones containing open or latent anti-Semitism. After the end of the war, and until his death, Weber kept working on critical art concerning politics, justice, and the environment.

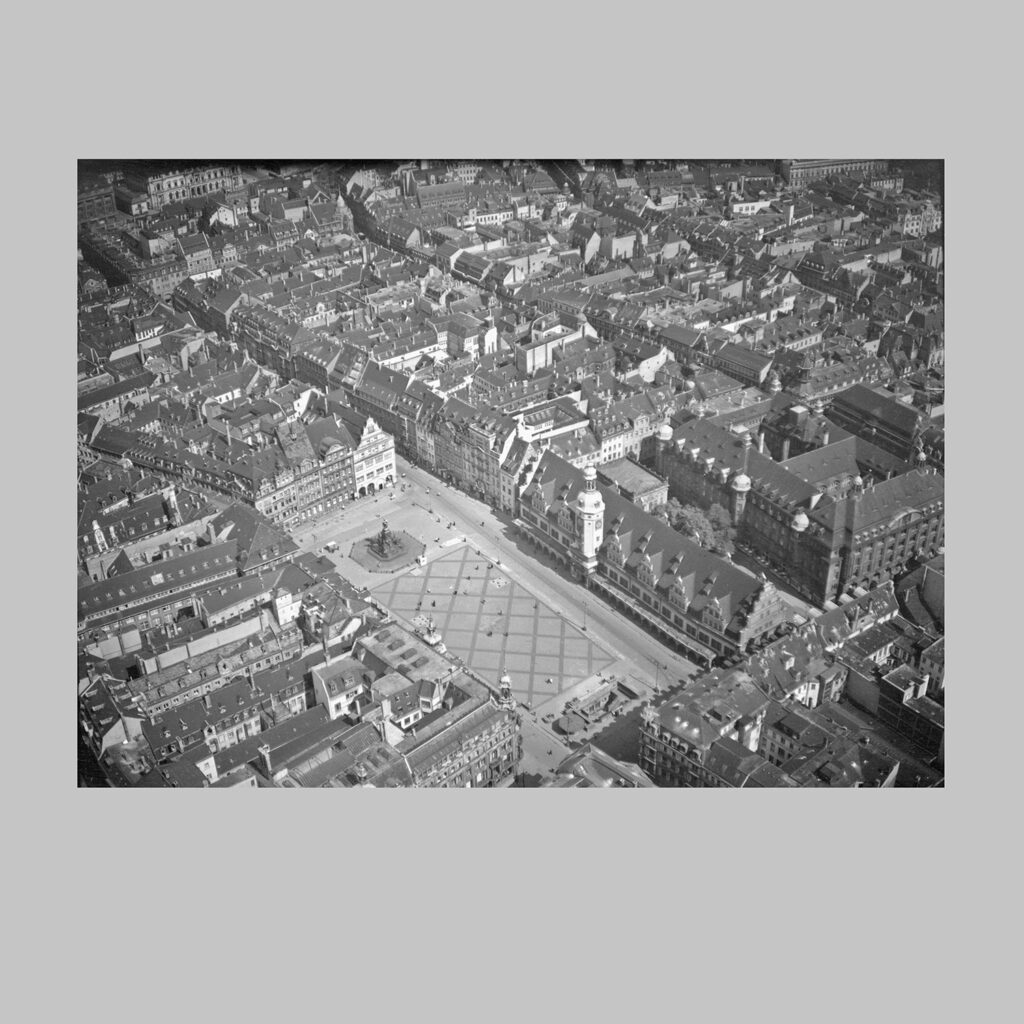

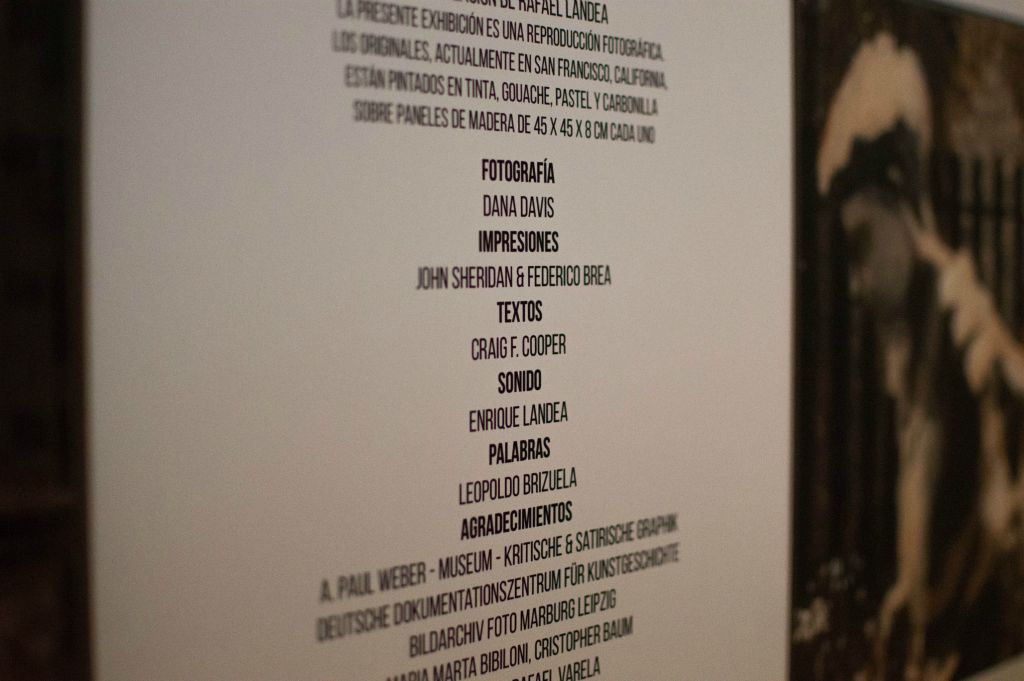

Photograph of Leipzig

Deutsche Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte – Bildarchiv Foto

Marburg / Leipzig: The market square and town hall before the first allied bombing raids over the city in December 1943.

The Weimar Republic Era (1919-1933) always generates a particular fascination with me. A little more than a decade of democracy in Germany between wars contained a great and dense social, economic and political history in the context of a nation with a tradition strongly inspired in the authoritarian-imperialistic model.

Despite the attempt to institute democratic principles, Germany never felt identified with that experiment of equality and participation, and it seemed destined that it was going to end in the worst way, creating from its core nature the most bloody totalitarian regime in recent history.

It was a time of true convulsion. Not only for the desperate conditions Germany endured following its surrender after World War I, but also due to the humiliating and disproportionate conditions the victors imposed, conditions that brought the nation to its knees. To this we must add the enormous repercussions of the fall of the czarist dynasty in Russia that were felt throughout all of Europe, and its cruel replacement by a communist state, a process that was unfolding like an inescapable backdrop during the initial years of the Weimar Republic. The Russian communist state, perhaps the most momentous political event in the history of the 20th century, generated support among intellectuals, political leaders, and especially the German working class as it did horror in the dominant elite class, landowners and the petit bourgeoisie. This tension decisively influenced the Weimar political scene until it was finally resolved by its collapse on January 30, 1933 with the rise of the radically anti-Communist option embodied by Hitler and the NSDAP. As throughout any period of history spanned by convulsions and contradictions, the Weimar era was very prolific in terms of the arts and culture. These were years illuminated – forever – by writers, theater and movie directors, musicians, painters and sculptors. Venues for dance, fun, and morally prohibited activities flourished.

This cultural and artistic expansion provided refuge, an escape from the oppressive reality; an impression that, despite the “normality” of a developing, formal democracy, something very profound was amiss, a dormant authoritarianism maintained artificially in a state of latency, a monster – well captured by Rafael Landea – which haunts city streets like a ghost that appears in dreams but that at any moment could rouse us from our deep sleep

Upon viewing this collection of paintings, where first we see images of routine tranquility and then secondly the approaching horror (or vice versa), I cannot erase from my mind each person depicted: the young men, the women, and the children and in my imagination I transport them to the next decade. Absolutely none of them will escape a tragic fate under Nazi dictatorship in a Germany marching toward war. As Borges said in Deutsches Requiem, “the exhilarating glory will be given to him first and then the bitter defeat.”

I believe that this is the point that Rafael Landea’s paintings capture with subtlety, and which constitutes a universal theme: images of everyday life, the jovial faces, a feeling of nonchalance in the face of the tragedy that lies ahead. As an observer, one feels an impulse to enter into a dialogue with these figures, to warn them, to shake them, to scream at them until they come to their senses, but their fate had already been written and all of them will be consumed in a bonfire of the inevitable. After this irrational impulse comes a necessary and profound reflection that leads us to wonder if, in one way or another, each one of us is currently being recorded as images. Perhaps new observers will want to warn us, with the same desperation, about the danger that hangs over our own existence. Is it that nothing has changed for the Angel of History (that Benjamin discovers in Paul Klee’s 1920 painting, Angelus Novus): “His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

Surely these paintings by Rafael Landea allow us to put ourselves in that moment where Benjamin confronts the Angel of History…a necessary and urgent task in these fast-paced and tumultuous times.

Buenos Aires, May 2016

*Daniel Rafecas is an attorney and has a PhD in Criminal Science from the University of Buenos Aires. Since 2004, Mr. Rafecas has been working as a federal judge with purview over criminal cases against humanity arising from Argentina’s last military dictatorship. He has presented at many conferences concerning the Shoah in the United States, France, Spain, Israel and several Latin American countries. He authored the books “History of the Final Solution. An investigation of the stages that led to the extermination of the European Jews” (Twentieth Century, 2012), “Torture and other illegal practices of detainees. A reflection on the Argentine Penal Code” (Editores del Puerto: Buenos Aires, 2010)

Media

The paintings are sepia-tinted, gouache and ink on wood.

The drawings are black & white, charcoal and pastel on wood.

Paintings and Drawings

There are ten (10) paintings and nine (9) drawings (see table below).

Dimensions

Each image consists of two to ten individual wooden panels (see table below).

Each panel measures 18in. /18in. / 1in. (45.7cm/45.7cm/2.5cm).

The total installation of artistic material covers an area of 166.8 sq ft (15.5 sq meters). If you allow for typical spacing between paintings and drawings, a total of 172 sq feet (16 sq meters) of gallery space is needed (not including introductory panels).

Installation Options

The drawings and paintings are typically installed in an alternating fashion in one long horizonal frieze. However, the wooden panel “puzzle” pieces allow for a multiple installation options based on gallery space availability and constraints. The wooden panels are lightweight allowing for easy, straight-forward installation.

Play Video

1930, the room

Play Video

1930, the kid

Play Video

Rafael Landea received his MFA from La Plata University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is a 2011 recipient of a San Francisco Arts Commission Grant for Individual Artists and he was featured in the 2012 “Our Radar”, Creative Capital database of art projects.

His works are included in the public collections at MaM (Museum of Art and Memory), and MPB (Fine Arts Museum Buenos Aires) Argentina.

His most recent solo exhibitions were “1930” Buenos Aires Holocaust Museum, “Maps of Silence”, a multimedia installation at the Exploratorium Museum of Art Science and Human Perception in San Francisco, and “Malvinas” Museum Malvinas (ESMA) Buenos Aires.

Other solo exhibition venues include Grace Cathedral 1055 Gallery, San Francisco, CA, and, Archimboldo Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Group exhibition highlights include “Performance” at Gensler San Francisco, “Madres de Plaza de Mayo” CC Haroldo Conti, Buenos Aires.

Landea has worked as a set designer and painter for theater in Argentina for more than 15 years. He has also been actively involved in designing and producing murals nationally and internationally; the latest in San Francisco, funded by Artery Project, and collaborations in Turin and Genoa, Italy.

In 2019 created two large murals, Architecture University and the Law Library both in La Plata, Argentina.

He has created illustrations for magazines and books for important Argentinean publishers as Anfibia, Malisia, EME, Ediciones B, and Universities, the latest in 2021: “Malvinas mi Casa” a book based on a diary written in 1829 in Malvinas/Falklands.

Landea was selected for the 2020 Prequalified Artist Pool by San Francisco Arts Commission.

Rafael Landea received his MFA from La Plata University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is a 2011 recipient of a San Francisco Arts Commission Grant for Individual Artists and he was featured in the 2012 “Our Radar”, Creative Capital database of art projects.

His works are included in the public collections at MaM (Museum of Art and Memory), and MPB (Fine Arts Museum Buenos Aires) Argentina.

His most recent solo exhibitions were “1930” Buenos Aires Holocaust Museum, “Maps of Silence”, a multimedia installation at the Exploratorium Museum of Art Science and Human Perception in San Francisco, and “Malvinas” Museum Malvinas (ESMA) Buenos Aires.

Other solo exhibition venues include Grace Cathedral 1055 Gallery, San Francisco, CA, and, Archimboldo Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Group exhibition highlights include “Performance” at Gensler San Francisco, “Madres de Plaza de Mayo” CC Haroldo Conti, Buenos Aires.

Landea has worked as a set designer and painter for theater in Argentina for more than 15 years. He has also been actively involved in designing and producing murals nationally and internationally; the latest in San Francisco, funded by Artery Project, and collaborations in Turin and Genoa, Italy.

In 2019 created two large murals, Architecture University and the Law Library both in La Plata, Argentina.

He has created illustrations for magazines and books for important Argentinean publishers as Anfibia, Malisia, EME, Ediciones B, and Universities, the latest in 2021: “Malvinas mi Casa” a book based on a diary written in 1829 in Malvinas/Falklands.

Landea was selected for the 2020 Prequalified Artist Pool by San Francisco Arts Commission.